VIRGINIA WOOLF (1882-1941):

A SHORT BIOGRAPHY

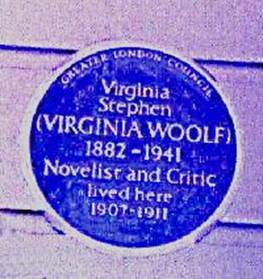

For a plaque to be associated with a person, his/her

name must be known to the well-informed passer-by, but no plaque will be

erected until a person has been dead for 20 years or until the centenary of

their birth (whichever is the earlier) and plaques will not be erected on the

sites of former houses.

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born on 25 January 1882 in London. Her father,

Leslie Stephen (1832-1904), was a man of letters (and first editor of the

Dictionary of National Biography) who came from a family distinguished for

public service (part of the ‘intellectual aristocracy' of Victorian England).

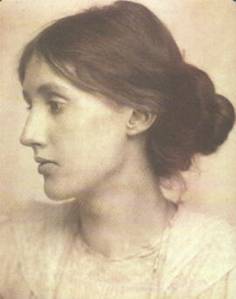

Her mother, Julia (1846-95), from whom Virginia inherited her looks, was the

daughter and niece of the six beautiful Pattle sisters (Julia Margaret Cameron

was the seventh: not beautiful but the only one remembered today). Both parents

had been married before: her father to the daughter of the novelist, Thackeray,

by whom he had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who was intellectually backward;

and her mother to a barrister, Herbert Duckworth (1833-70), by whom she had

three children, George (1868-1934), Stella (1869-97), and Gerald (1870-1937).

Julia and Leslie Stephen had four children: Vanessa (1879-1961), Thoby (1880-1906),

Virginia, and Adrian (1883-1948). All eight children lived with the parents and

a number of servants at 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington. Long summer holidays

were spent at Talland House in St Ives, Cornwall, and St Ives played a large

part in Virginia’s imagination. It was the setting for her novel To the

Lighthouse, despite its ostensibly being placed on the Isle of Skye. London

and/or St Ives provided the principal settings of most of her novels. In 1895

her mother died unexpectedly, and Virginia suffered her first mental breakdown.

Her half-sister Stella took over the running of the household as well as coping

with Leslie’s demands for sympathy and emotional support. Stella married Jack

Hills in 1897, but she too died suddenly on her return from her honeymoon. The

household burden then fell upon Vanessa. Virginia was allowed uncensored access

to her father’s extensive library, and from an early age determined to be a

writer. Her education was sketchy and she never went to school. Vanessa trained

to become a painter. Their two brothers were sent to preparatory and public

schools, and then to Cambridge. There Thoby made friends with Leonard Woolf,

Clive Bell, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Lytton Strachey, and Maynard Keynes. This was

the nucleus of the Bloomsbury Group. Leslie Stephen died in 1904, and Virginia

had a second breakdown. While she was sick, Vanessa arranged for the four

siblings to move from 22 Hyde Park Gate to 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury. At the

end of the year Virginia started reviewing with a clerical paper called the

Guardian; in 1905 she started reviewing in The Times Literary Supplement

and continued writing for that journal for many years. Following a trip to

Greece in 1906, Thoby died of typhoid and in 1907 Vanessa married Clive Bell.

Adeline Virginia Stephen was born on 25 January 1882 in London. Her father,

Leslie Stephen (1832-1904), was a man of letters (and first editor of the

Dictionary of National Biography) who came from a family distinguished for

public service (part of the ‘intellectual aristocracy' of Victorian England).

Her mother, Julia (1846-95), from whom Virginia inherited her looks, was the

daughter and niece of the six beautiful Pattle sisters (Julia Margaret Cameron

was the seventh: not beautiful but the only one remembered today). Both parents

had been married before: her father to the daughter of the novelist, Thackeray,

by whom he had a daughter Laura (1870-1945) who was intellectually backward;

and her mother to a barrister, Herbert Duckworth (1833-70), by whom she had

three children, George (1868-1934), Stella (1869-97), and Gerald (1870-1937).

Julia and Leslie Stephen had four children: Vanessa (1879-1961), Thoby (1880-1906),

Virginia, and Adrian (1883-1948). All eight children lived with the parents and

a number of servants at 22 Hyde Park Gate, Kensington. Long summer holidays

were spent at Talland House in St Ives, Cornwall, and St Ives played a large

part in Virginia’s imagination. It was the setting for her novel To the

Lighthouse, despite its ostensibly being placed on the Isle of Skye. London

and/or St Ives provided the principal settings of most of her novels. In 1895

her mother died unexpectedly, and Virginia suffered her first mental breakdown.

Her half-sister Stella took over the running of the household as well as coping

with Leslie’s demands for sympathy and emotional support. Stella married Jack

Hills in 1897, but she too died suddenly on her return from her honeymoon. The

household burden then fell upon Vanessa. Virginia was allowed uncensored access

to her father’s extensive library, and from an early age determined to be a

writer. Her education was sketchy and she never went to school. Vanessa trained

to become a painter. Their two brothers were sent to preparatory and public

schools, and then to Cambridge. There Thoby made friends with Leonard Woolf,

Clive Bell, Saxon Sydney-Turner, Lytton Strachey, and Maynard Keynes. This was

the nucleus of the Bloomsbury Group. Leslie Stephen died in 1904, and Virginia

had a second breakdown. While she was sick, Vanessa arranged for the four

siblings to move from 22 Hyde Park Gate to 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury. At the

end of the year Virginia started reviewing with a clerical paper called the

Guardian; in 1905 she started reviewing in The Times Literary Supplement

and continued writing for that journal for many years. Following a trip to

Greece in 1906, Thoby died of typhoid and in 1907 Vanessa married Clive Bell.  Thoby had started ‘Thursday evenings' for his friends to visit, and this

kind of arrangement was continued after his death by Vanessa and then by

Virginia and Adrian when they moved to 29 Fitzroy Square. In 1911 Virginia

moved to 38 Brunswick Square. Leonard Woolf had joined the Ceylon Civil Service

in 1904 and returned in 1912 on leave. He soon decided that he wanted to marry

Virginia, and she eventually agreed. They were married in St Pancras Registry

Office on 10 August 1912. They decided to earn money by writing and journalism.

Since about 1908 Virginia had been writing her first novel The Voyage Out

(originally to be called Melymbrosia). It was finished by 1913 but,

owing to another severe mental breakdown after her marriage, it was not

published until 1915 by Duckworth & Co. (Gerald’s publishing house). The

novel was fairly conventional in form. She then began writing her second novel Night

and Day - if anything even more conventional - which was published in 1919,

also by Duckworth. From 1911 Virginia had rented small houses near Lewes in

Sussex, most notably Asheham House. Her sister Vanessa rented Charleston

Farmhouse nearby from 1916 onwards. In 1919 the Woolfs bought Monks House in

the village of Rodmell. This was a small weather-boarded house (now owned by

the National Trust) which they used principally for summer holidays until they

were bombed out of their flat in Mecklenburgh Square in 1940 when it became

their home. In 1917 the Woolfs had bought a small hand printing-press in order

to take up printing as a hobby and as therapy for Virginia. By now they were

living in Richmond (Surrey) and the Hogarth Press was named after their house.

Virginia wrote, printed and published a couple of experimental short stories, The

Mark on the Wall and Kew Gardens. The Woolfs continued handprinting

until 1932, but in the meantime they increasingly became publishers rather than

printers. By about 1922 the Hogarth Press had become a business. From 1921

Virginia always published with the Press, except for a few limited editions.

Nineteen-twenty-one saw Virginia’s first collection of short stories Monday

or Tuesday, most of which were experimental in nature. In 1922 her first

experimental novel, Jacob’s Room, appeared. In 1924 the Woolfs moved

back to London, to 52 Tavistock Square. In 1925 Mrs. Dalloway was

published, followed by To the Lighthouse in 1927, and The Waves

in 1931. These three novels are generally considered to be her greatest claim

to fame as a modernist writer. Her involvement with the aristocratic novelist

and poet Vita Sackville-West led to Orlando (1928), a roman à clef

inspired by Vita’s life and ancestors at Knole in Kent. Two talks to women’s

colleges at Cambridge in 1928 led to A Room of One’s Own (1929), a

discussion of women’s writing and its historical economic and social

underpinning. The 1930s was a less happy time for the Woolfs as the deaths of

friends and the prospect of war increasingly overshadowed the decade. Virginia

produced Flush (1933), a fictional biography of Elizabeth Barrett

Browning’s dog; The Years (1937), a family saga (more unconventional

than that sounds) which was a best-seller in America but had been a long and

painful time in the writing; Three Guineas (1938), in a sense a

successor to A Room of One’s Own; and in 1940 a biography of her friend

Roger Fry who had died in 1934. She had practically completed her final novel Between

the Acts when she committed suicide by drowning in the River Ouse near

Monks House on 28 March 1941.

Thoby had started ‘Thursday evenings' for his friends to visit, and this

kind of arrangement was continued after his death by Vanessa and then by

Virginia and Adrian when they moved to 29 Fitzroy Square. In 1911 Virginia

moved to 38 Brunswick Square. Leonard Woolf had joined the Ceylon Civil Service

in 1904 and returned in 1912 on leave. He soon decided that he wanted to marry

Virginia, and she eventually agreed. They were married in St Pancras Registry

Office on 10 August 1912. They decided to earn money by writing and journalism.

Since about 1908 Virginia had been writing her first novel The Voyage Out

(originally to be called Melymbrosia). It was finished by 1913 but,

owing to another severe mental breakdown after her marriage, it was not

published until 1915 by Duckworth & Co. (Gerald’s publishing house). The

novel was fairly conventional in form. She then began writing her second novel Night

and Day - if anything even more conventional - which was published in 1919,

also by Duckworth. From 1911 Virginia had rented small houses near Lewes in

Sussex, most notably Asheham House. Her sister Vanessa rented Charleston

Farmhouse nearby from 1916 onwards. In 1919 the Woolfs bought Monks House in

the village of Rodmell. This was a small weather-boarded house (now owned by

the National Trust) which they used principally for summer holidays until they

were bombed out of their flat in Mecklenburgh Square in 1940 when it became

their home. In 1917 the Woolfs had bought a small hand printing-press in order

to take up printing as a hobby and as therapy for Virginia. By now they were

living in Richmond (Surrey) and the Hogarth Press was named after their house.

Virginia wrote, printed and published a couple of experimental short stories, The

Mark on the Wall and Kew Gardens. The Woolfs continued handprinting

until 1932, but in the meantime they increasingly became publishers rather than

printers. By about 1922 the Hogarth Press had become a business. From 1921

Virginia always published with the Press, except for a few limited editions.

Nineteen-twenty-one saw Virginia’s first collection of short stories Monday

or Tuesday, most of which were experimental in nature. In 1922 her first

experimental novel, Jacob’s Room, appeared. In 1924 the Woolfs moved

back to London, to 52 Tavistock Square. In 1925 Mrs. Dalloway was

published, followed by To the Lighthouse in 1927, and The Waves

in 1931. These three novels are generally considered to be her greatest claim

to fame as a modernist writer. Her involvement with the aristocratic novelist

and poet Vita Sackville-West led to Orlando (1928), a roman à clef

inspired by Vita’s life and ancestors at Knole in Kent. Two talks to women’s

colleges at Cambridge in 1928 led to A Room of One’s Own (1929), a

discussion of women’s writing and its historical economic and social

underpinning. The 1930s was a less happy time for the Woolfs as the deaths of

friends and the prospect of war increasingly overshadowed the decade. Virginia

produced Flush (1933), a fictional biography of Elizabeth Barrett

Browning’s dog; The Years (1937), a family saga (more unconventional

than that sounds) which was a best-seller in America but had been a long and

painful time in the writing; Three Guineas (1938), in a sense a

successor to A Room of One’s Own; and in 1940 a biography of her friend

Roger Fry who had died in 1934. She had practically completed her final novel Between

the Acts when she committed suicide by drowning in the River Ouse near

Monks House on 28 March 1941.

"....purity or their impurity discussed. If you

start a society for pure English they will show their resentment by starting

another for impure English. Hence the unnatural violence of much modern

speech."

(

This is a very short extract from a broadcast she made on on 29th April, 1937,

later published in The Listener on 5th May 1937. Hussey ('A to Z of Virginia

Woolf') says that only part of this talk survives, that it is the only

surviving record of her voice, but that Quentin Bell 'has said it does not give

a very accurate idea of how she sounded'. )

Virginia Woolf's Psychiatric History

(from a study by Malcom Ingram)

PERSONALITY

There are many descriptions of her mature personality; indeed, the oral

and written recollections of twenty-eight friends, relatives and servants have

been published. They paint a consistent picture of an inconsistent individual.

She was a mixture of shyness and liveliness. She 'was shy and awkward, often

silent, or, if in the mood to talk, would leap into fantasy and folly and

terrify the innocent and unprepared.'(Angelica Garnett). She was 'enormously

generous.' 'Shop assistants made her feel shy and out of place'(ibid). Away

from social life, she was a workaholic like her father. 'Leonard has said that

of the sixteen hours of her waking life, Virginia was working fifteen hours in

one way or another.'(John Lehmann). Fellow writers elaborate on the extraverted

side of her character. Elizabeth Bowen noted that 'her power in conveying

enjoyment was extraordinary. And her laughter was entrancing. It was outrageous

laughter, almost a child's laughter. Whoops of laughter, if anything amused

her. ......She was awfully naughty. She was fiendish. She could say things

about people, all in a flash, which remained with one. Fleetingly malicious,

rather than outright cruel.' Rosamond Lehmann confirms all this: 'Her

conversation was a brilliant mixture of reminiscence, gossip, extravagantly

fanciful speculation and serious critical discussion of books and pictures. She

was malicious and she liked to tease.....she gave an impression of quivering

nervous excitement, of a spirit balanced at a pitch of intensity impossible to

sustain without collapse......She loved jokes, cracked them herself without

decorum, and laughed at those of others.' Her sense of fun showed in her

dealings with children. She was fond of them and they enjoyed her company. Her

future biographer, Quentin Bell, was one who, in childhood, looked forward to

her visits 'more than anything.' 'Virginia's coming - what fun we shall

have'.(Clive Bell) Frances Marshall says 'Argument was not her forte, but wild

generalisations based on the flimsiest premises and embroidered with elaborate

fantasy...' In a television interview in 1967 her husband said: '.....the way

that her mind worked when she was perfectly sane. First of all, in her own

conversation she would do what I called "leaving the ground".

Suddenly she would begin telling one something quite ordinary, and incident

she'd seen in the street or something like that; and when her mind seemed to

get completely off the ground she would give the most fascinating and amusing

description of something fantastic, quite unlike anything that anyone other than

herself would have thought of, which would last for about five or ten

minutes.'The young Stephen Spender often attended informal dinner parties given

by the Woolfs. 'When entertaining she would, at the start of the evening, be

nervous, preoccupied with serving the drinks. Her handshake and her smile of

welcome would perhaps be a little distraught.' He was surprised, in the

Thirties, that she often cooked and served the meal. She would often smoke a

cheroot after dinner. The talk would be of literature, sometimes of politics,

when she would fall silent and let the men talk. She loved to talk about social

class divisions, and about the Royal Family, sometimes to the point of tedium,

Spender thought. Despite her interest she did not approve of honours and refused

the C.H. proffered in 1935. Spender too saw her malicious side. She had one or

two friends she cast in the role of jester and told anecdotes about - Ethel

Smyth and Hugh Walpole were constant targets of gossip. The picture that

emerges from reminiscences is remarkably consistent. Socially she was a

talkative, formidably intelligent, witty, and humorous woman. With friends she

was talkative, given to flights of fancy, and fond of jokes and gossip. Even in

private she talked. When her new housekeeper arrived in 1934, she was

surprised: 'The floors in Monks House were very thin, the bathroom was directly

above the kitchen and when Mrs Woolf was having her bath before breakfast I

could hear her talking to herself. On and on she went, talk, talk, talk: asking

questions and giving herself the answers. I thought there must be two or three

people up there with her.....it startled me in the mornings for quite some

time'. She was often malicious. Shy at first in company, and ill at ease with

strangers and those outwith her circle and social class, she was warm and

affectionate with children and intimates. At times carried away by her

fantastical imagination, she had difficulty in projecting herself into others

work and lives and feelings. It was characteristic that she interrogated

everyone she met about the details of their lives. She wanted to know all the

details of peoples lives. "Now what did you do,exactly, what did you

do?", Elizabeth Bowen remembers her asking, both of adults and children,

making them scrutinise their lives, pinning them down, and of course provide

her with copy. Her love of fantasy led her to tease. If someone gave her a

humdrum account of a holiday abroad, she would invent adventures they must have

had, which became more and more extravagant and unlikely as they developed. Her

friends saw little of the depressive side of her nature, probably because

Leonard was ever alert for warning signs, and insisted that she withdraw from

social life immediately they appeared. And the history of her attacks suggests

that even when very depressed she could dissemble socially. There is nothing in

her friends' descriptions to suggest the oddity, the barrier to communication,

met with in the recovered schizophrenic. She could be rude at times, even

snobbish, but she never experienced the slightest difficulty in communication -

on the contrary. Friends delighted in her conversation, and many thought her

the wittiest conversationalist of a highly articulate circle. Mystical

experience was not part of her public persona, but she had strange feelings of

unreality when she was a child in 1894, looking at a puddle in Hyde Park

Gardens. She recalled this in her 1940 reminiscences:'when for no reason I

could discover, everything suddenly became unreal; I was suspended, I could not

step across a puddle: I tried to touch something.....the whole world became

unreal' She quotes the puddle in The Waves, and writes in her diary of the

'semi-mystic very profound life of a woman.' There are no other 'normal'

abnormal experiences in her life; all other psychological symptoms are related

in time and character to her affective illnesses.

VIRGINIA WOOLF - SUICIDE

On the 28th March, 1941,

aged fifty-nine, she drowned herself in the river Ouse, near her Sussex home.

Two suicide notes were found in the house, similar in content; one may have

been written ten days earlier, and it is possible that she may have made an

unsuccessful attempt then, for she returned from a walk soaking wet, saying

that she had fallen. They were addressed to her sister Vanessa and to her

husband Leonard. To him, she wrote:

On the 28th March, 1941,

aged fifty-nine, she drowned herself in the river Ouse, near her Sussex home.

Two suicide notes were found in the house, similar in content; one may have

been written ten days earlier, and it is possible that she may have made an

unsuccessful attempt then, for she returned from a walk soaking wet, saying

that she had fallen. They were addressed to her sister Vanessa and to her

husband Leonard. To him, she wrote:

'Dearest, I feel certain

I am going mad again. I feel we can't go through another of those terrible

times. And I shan't recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't

concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me

the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone

could be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this terrible

disease came. I can't fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life,

that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can't even write

this properly. I can't read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of

my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I

want to say that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would

have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness.

I can't go on spoiling your life any longer. I don't think two people could have

been happier than we have been.

V.'

After writing this note she left Monk's House, Rodmell - her home - at

11.30 am, taking her walking stick, and crossed the water meadows to the river,

where she put a large stone in the pocket of her coat. Her body was not

recovered until the 18th April when it was discovered by children a short way

downstream. Her husband identified the body, and an inquest was held the

following day at Newhaven. The verdict, in the standard phrase of the time, was

'suicide while the balance of her mind was disturbed.' She was cremated

privately at Brighton on 21st April, and her ashes scattered under one of the

pair of elms at Monk's House.

SEX

Virginia Woolf was

sexually abused as a child. She told her family about it, she wrote about it in

letters, diaries and memoirs, and her sisters, also abused, confirmed it.

Whether these childhood experiences had any relationship to her later illnesses

is questionable, but they had undeniable effects on her adult sexuality, her

psychological make-up and her writing. The details of the abuse are

difficult to determine. They involved, at different times, her stepbrothers,

George and Gerald Duckworth. Fifty years on, the memory was fresh even when she

wrote to Ethel Smyth in January 1941: '......it's like breaking the hymen...I

still shiver with shame at the memory of my half brother, standing me on a

ledge, aged about six, and so exploring my private parts. Why should I have

felt shame then?' But the major malefactor was the other brother George, fourteen

years her senior; 'my incestuous brother` Virginia called him in a letter of

1936. This need not be accepted at its face value; she was prone to exaggerate

in conversation and in correspondence with the family. De Salvo, author of a

book on the impact of sexual abuse on her life and work, claims that all the

siblings - Virginia, Laura, Stella, Vanessa and Stella - were subjected to

'incest'. That this was common family knowledge is implicit in Virginia's

comment to her sister in a letter of May 1934, after hearing of George

Duckworth's death: 'Leonard says Laura is the one we could have spared.' De

Salvo claims that George sexually abused Virginia over nine or ten years until

1903 or 1904 - throughout her teenage years, from the age of twelve to

twenty-one. The first reference to these events is in a typically flippant

letter to her sister Vanessa in 1911, describing how she told her Greek teacher

Janet Case about George. 'This led to the revelation of all George's

malefactions. To my surprise she (Janet Case) has always had an intense dislike

of him; and used to say "Whew you nasty creature," when he came in

and began fondling me over my Greek. When I got to the bedroom scenes, she

dropped her lace, and gaped like a benevolent gudgeon. By bedtime she was feeling

quite sick, and did go to the WC which, needless to say, had no water in it.'

Her nephew Quentin Bell did not suppress these events when he wrote her

biography. He had statements from her husband and from Dr Noel Richards, and

dated George's 'malefactions' from the time of the death of Virginia's mother,

in 1895, when Virginia was thirteen. Virginia herself later described these

activities, whatever their exact nature, continuing in 1903 or 1904, when she

would be twenty-one. She said later that George had spoilt her life before it

had begun, and that she had no enjoyment of her body. She also related these

problems, not only to the two step-brothers but also to her father, who had

'made too great emotional claims upon me, and that I think has accounted for

many of the wrong things in my life.... I never remember any enjoyment of my

body.' After their mother's death George consoled the sisters, spent time with

them. and was generally regarded as devoted to them. He also fondled them, in

public, and in their bedrooms. Vanessa and Virginia were savage in their

comments about him for the rest of his life. He dominated their lives for

years. 'George was thirty-six when I was twenty. And he had a thousand pounds a

year whereas I had fifty. These were good reasons why it was difficult not to

submit to whatever he decreed.'(Moments of Being) At the time of Virginia's

breakdown after her father's death, Vanessa was concerned enough to report

George's activities to the specialist treating her sister, Dr Savage, who took

them serously enough to speak to George. Her sexual feelings were affected for

the rest of her life. as can be traced during her engagement and marriage. When

she wrote to accept his proposal on 1 5 12 she told Leonard bluntly that she

had no sexual feelings for him. '.....is it the sexual side that comes between

us? As I told you brutally the other day, I feel no physical attraction in you.

There are moments - when you kissed me the other day was one - when I feel no

more than a rock. And yet your caring for me as you do overwhelms me. ...' From

her honeymoon she wrote to Ka Cox making clear that she was not enthralled with

the sexual act, and on their return the couple consulted her sister Vanessa,

who immediately reported it in a letter about the 'Goat's coldness'.

'Apparently she still gets no pleasure at all from the act, which I think is

curious.' At the time Vanessa blamed George Duckworth, but sexual abuse from

the same source seems to have had no effect on her own adult sexual life.

Despite her lack of sexual response the new Mrs Woolf hoped to have children.

In October 1912 she thanked Violet Dickinson for sending a cradle - 'My baby

shall sleep in the cradle.' Nigel Nicolson, introducing the letters from this

period, says confidently that 'their love was not at first sexless. For two or

three years they shared a bed and for several more a bedroom, and it was only

on medical advice that they decided not to have children.' Despite their sexual

difficulties the marriage was a happy one, as both repeatedly made clear over

the years - and Virginia at the end of her life in her suicide note. They had

pet names and a private language. She was his ugly monkey, the mandril, while

he was the pathetic servant mongoose. When she became ill he became the Master

and was the dominant partner. Her feelings about sex may well have coloured her

attitude to Freud. Although her firm was the first to publish Freud in English,

and her younger brother Adrian Stephen and his wife Karen were among the first

British psychoanalysts, she was profoundly sceptical about Freud's work for

most of her life. In October 1924, she mentions in a letter that 'we are

publishing all Dr Freud, and I glance at the proof and read how Mr A.B. threw a

bottle of red ink on to the sheets of his marriage bed to excuse his impotence

to the housemaid, but threw it in the wrong place, which unhinged his wife's

mind, and to this day she pours claret on the dinner table. We could all go on

like that for hours; and yet these Germans think it proves something - besides

their own gull-like imbecility.' Similarly a 1920 review- Freudian Fiction -

also shows her teasing attitude to psychoanalysis: 'A patient who has never

heard a canary sing without falling down in a fit can now walk through an

avenue of cages without a twinge of emotion since he has faced the fact that

his mother kissed him in the cradle. The triumphs of science are beautifully

positive.' A Freudian would be intrigued by the odd example she gives, and

point out that she heard the birds singing in Greek when she was psychotic in

her teenage years. As the years passed she became less hostile. She met

psychoanalysts like John Rickman at dinner parties through her brother and his

wife, and enjoyed discussion of psychological topics. In Three Guineas, written

in 1937, she uses some Freudian terms. In 1939 and 1940, when she was writing

about her father, she began to read Freud, and discovered with surprise that

her ambivalent relationship to her father was no news to him. She had met the

great man in 1939 eight months before his death. He invited her and Leonard to

afternoon tea in his Hampstead home, was very courteous, and presented Virginia

with a narcissus, one hopes with no symbolic overtones. During her life

Virginia Woolf had several intense friendships with women, mostly older. Some,

like Vita Sackville West, a lesbian, were sexual, but it is unlikely that any

of these affairs were carnal, although Vita claimed to have gone to bed with

Virginia twice. In 1926 she wrote to her husband Harold Nicolson:'..I am scared

to death of arousing physical feelings in her, because of the madness. I don't

know what effect it would have, you see; it is a fire with which I have no wish

to play. I have too much real affection and respect for her. Also she has never

lived with anyone except Leonard, which was a terrible failure, and was

abandoned quite soon.' For her generation, Virginia was - in language at least

- remarkably uninhibited and 'liberated' in sexual matters. She went swimming

in the nude with Rupert Brooke, she typed bawdy material for Lytton Strachey,

and she wrote to her sister about Leonard's wet dreams without restraint. And

yet she writes late in her life, to Ethel Smyth, her last close female friend:

'...but I was always sexually cowardly, my terror of real life has always kept

me in a nunnery.' Three areas of her life and experience are relevant to her

sexual life: her childhood sexual experiences, her manic depressive illness,

and her personality. It seems likely that she was sexually frigid, in practice,

but sexually liberated in theory, and intellectually. At times when she was

elated, grossly or mildly, she was probably more disinhibited in conversation,

but the illness does not seem to have increased her sexual drive in terms of

sexual activity. Those who stress the importance of her childhood sexual abuse

have every right to do so in this area of her adult sexuality, which was

certainly warped by her childhood misfortunes, even if the same experiences

seem to have had much less effect on her sister Vanessa.