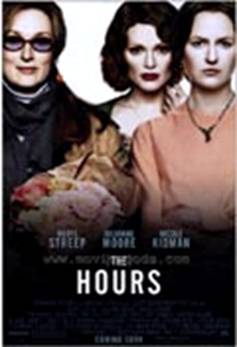

THE MOVIE

The Hours is the

story of three women searching for more potent, meaningful lives. Each is alive

at a differrent time and place; all are linked by their yearnings and their

fears. Virginia Woolf in a suburb of London in the early 1920’s, is battling

insanity as she begins to write her first great novel, “Mrs. Dalloway”. Laura

Brown, a wife and mother in Los Angeles at the end of the World War Two, is

reading “MRs.Dalloway”, and finding it so revelatory that she begins to

consider making a devastating change in her life. Clarissa Vaughan, a

contemporary version of Mrs.Dalloway, lives in New York City today, and is in

love with her frined Richard, a brilliant poet who is dying of AIDS.

Their stories

interwine, and finally come together in a surprising, trascnedent mometn of

shared recognition.

THE HEROICS OF EVERYDAY LIVES - Director Stephen Daldry on THE HOURS

I read David Hare’s

screenplay for THE HOURS before I had read Michael Cunningham’s novel. My first

response was that this was a fantastically wellachieved screenplay, which moved

seamlessly through time and three different women’s lives. The same was true

for the novel, which I read next. Both were rich and multi-faceted – about life

and death, mothers and sons, art and madness,memories and regrets. Ultimately,

I saw the story as being about the cost of different choices a person makes –

the cost of being a caregiver trying to give a dying person dignity; of being a

mother who has no choice but to change her life; of being an artist risking

insanity for the sake of creation – and how the consequences of those choices

can be very high. I was particularly drawn to the script because it was a

wonderful opportunity to explore a single day in the lives of three women. For

me, the idea was that the voyages these women take moment by moment are

courageous. Often, I think, the heroics in women’s lives are silenced and take

place behind the scenes and are overshadowed by the public heroics of men. But

the struggles of these women are equally monumental and profound. From the

outset, Michael Cunningham told us that we should feel free to do whatever we

felt was appropriate with the book, which was very liberating. Towards the end

of filming, Scott Rudin, David Hare and myself all re-read the book to make sure

that we hadn’t missed anything and based on that last reading we made some final

re-writes. The book always informed the production. However, the movie was never

locked into a strict adaptation, which created a perfect relationship. An

important aspect of the filming process was to be true to the spirit of

Virginia Woolf, which is everywhere in the book and screenplay. Certainly if

you’ve never encountered Virginia Woolf or the novel "Mrs. Dalloway",

it makes no difference to the enjoyment of the film. But those who have read

"Mrs. Dalloway" know what a treasure trove it is, and I hope they will

find as much joy in the exploration as we did. Although there isn’t a lot of

natural physical similarity between Nicole Kidman and Virginia Woolf, they have

a similar animal magnetism - a danger and alertness. Because Nicole couldn’t

look exactly like Virginia Woolf, we tried instead to create the essence of

what that extraordinary face was like. Since I come from a theatre background,

rehearsal allows me a chance to work out the internal dynamics, the emotion of

a scene, and from that I can work where the camera should or shouldn’t be. One

of the great joys of rehearsing and knowing the screenplay for THE HOURS so

well before we shot it was knowing the cutting pattern from story to story. Rhythmically,

what you see on the screen is pretty much what we rehearsed, which is unusual. In

a sense, for THE HOURS, we were rehearsing three films at once, as we never

rehearsed Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman or Julianne Moore at the same time. There

was also great joy in having David at the rehearsals, ready to re-write from

the input of the actors, and directly to their strengths and weaknesses. The

fantastic cast truly brought these stories to life – their professionalism,

effort and care was astounding. We were blessed to not only have Meryl,

Julianne and Nicole, but also a supporting cast of unusual ability and talent. It

was a great pleasure to watch all their very different individual methods of

working blend together seamlessly. Ultimately, THE HOURS was a deeply

collaborative process between all the participants. The level of collective

creativity was quite remarkable – it was a true team effort. Most importantly,

we were lucky to have a group of actors who had worked extensively in the

theatre and were used to this way of working. They were able to participate in

the rehearsal process in a way that David Hare and I found incredibly useful. During

production, one of the most difficult sequences to shoot was the drowning of Virginia

Woolf. Nicole Kidman was aware that we would have to put her in a real river

with a fast current, and she was going to have to get under water and stay under

water. It was a seriously dangerous situation. But as far as Nicole was

concerned, there was never any question that anybody else would do it. That

sequence took several days to film, including the part where Virginia's body

has to be dragged along by the current on the bed of the river. When you see

those shots in the film, it is Nicole Kidman. She wouldn't have it any other

way. One thing we knew we always wanted on THE HOURS was to have not only a

coherence and unity in the overall look and design of the film, but at the same

time to have a different and distinctive look from story to story. There is a

visual opposition at work between the lives of the three women – and a lot of

that is done with simple elements such as color. We used a different palette

for Meryl, Julianne and Nicole but simultaneously, the colors in each of their

stories refer back to one another, providing little echoes from scene to scene.

We did similar things with camera movements and film processing techniques –

giving each woman and era a unique look yet one that is always tied to the next

story and the next moment in time. In the end, I think the film calls for a

very complex emotional reaction, and a different reaction to each story. One

thing that really interested me is the exploration of the mother-son

relationship, which is very complex, and comes to the fore in the story of

Laura Brown. In this case, you have a child who is literally deserted by his mother

– "abandoned" is the word that the mother herself uses. And our

individual response to that sort of act comes from a political, moral and

emotional place, especially because in our society mothers who leave their

children are judged severely. I think the response of each audience member to

Laura’s story will be different depending on their own personal experience or

personal knowledge of that sort of situation. But no matter where you are

starting from, I think everyone can relate in some way to the mother-son

relationship and will feel how potent it is and will be engaged by it. Another

interesting role many people will be able to relate to is that of Clarissa Vaughan

as the woman who looks after others in the hopes that creating happiness for

someone else will in turn create more meaning in her own life. There are

millions and millions of "carers" in this world who go unsung and

unexplored for the most part. I think many people will have a strong reaction

to Clarissa and the consequences of her choices. And then of course there is

Virginia Woolf, who is willing to literally risk her own sanity, risk

descending into madness, as an essential element in the creative process –

another choice that is open to debate and different responses. In this sense,

the film really is an exploration of women in the 20th century and the difficult,

sometimes heartbreaking, choices that they have had to make. For Laura, Clarissa

and Virginia Woolf, the choices are literally a matter between death and celebrating

life.

I read David Hare’s

screenplay for THE HOURS before I had read Michael Cunningham’s novel. My first

response was that this was a fantastically wellachieved screenplay, which moved

seamlessly through time and three different women’s lives. The same was true

for the novel, which I read next. Both were rich and multi-faceted – about life

and death, mothers and sons, art and madness,memories and regrets. Ultimately,

I saw the story as being about the cost of different choices a person makes –

the cost of being a caregiver trying to give a dying person dignity; of being a

mother who has no choice but to change her life; of being an artist risking

insanity for the sake of creation – and how the consequences of those choices

can be very high. I was particularly drawn to the script because it was a

wonderful opportunity to explore a single day in the lives of three women. For

me, the idea was that the voyages these women take moment by moment are

courageous. Often, I think, the heroics in women’s lives are silenced and take

place behind the scenes and are overshadowed by the public heroics of men. But

the struggles of these women are equally monumental and profound. From the

outset, Michael Cunningham told us that we should feel free to do whatever we

felt was appropriate with the book, which was very liberating. Towards the end

of filming, Scott Rudin, David Hare and myself all re-read the book to make sure

that we hadn’t missed anything and based on that last reading we made some final

re-writes. The book always informed the production. However, the movie was never

locked into a strict adaptation, which created a perfect relationship. An

important aspect of the filming process was to be true to the spirit of

Virginia Woolf, which is everywhere in the book and screenplay. Certainly if

you’ve never encountered Virginia Woolf or the novel "Mrs. Dalloway",

it makes no difference to the enjoyment of the film. But those who have read

"Mrs. Dalloway" know what a treasure trove it is, and I hope they will

find as much joy in the exploration as we did. Although there isn’t a lot of

natural physical similarity between Nicole Kidman and Virginia Woolf, they have

a similar animal magnetism - a danger and alertness. Because Nicole couldn’t

look exactly like Virginia Woolf, we tried instead to create the essence of

what that extraordinary face was like. Since I come from a theatre background,

rehearsal allows me a chance to work out the internal dynamics, the emotion of

a scene, and from that I can work where the camera should or shouldn’t be. One

of the great joys of rehearsing and knowing the screenplay for THE HOURS so

well before we shot it was knowing the cutting pattern from story to story. Rhythmically,

what you see on the screen is pretty much what we rehearsed, which is unusual. In

a sense, for THE HOURS, we were rehearsing three films at once, as we never

rehearsed Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman or Julianne Moore at the same time. There

was also great joy in having David at the rehearsals, ready to re-write from

the input of the actors, and directly to their strengths and weaknesses. The

fantastic cast truly brought these stories to life – their professionalism,

effort and care was astounding. We were blessed to not only have Meryl,

Julianne and Nicole, but also a supporting cast of unusual ability and talent. It

was a great pleasure to watch all their very different individual methods of

working blend together seamlessly. Ultimately, THE HOURS was a deeply

collaborative process between all the participants. The level of collective

creativity was quite remarkable – it was a true team effort. Most importantly,

we were lucky to have a group of actors who had worked extensively in the

theatre and were used to this way of working. They were able to participate in

the rehearsal process in a way that David Hare and I found incredibly useful. During

production, one of the most difficult sequences to shoot was the drowning of Virginia

Woolf. Nicole Kidman was aware that we would have to put her in a real river

with a fast current, and she was going to have to get under water and stay under

water. It was a seriously dangerous situation. But as far as Nicole was

concerned, there was never any question that anybody else would do it. That

sequence took several days to film, including the part where Virginia's body

has to be dragged along by the current on the bed of the river. When you see

those shots in the film, it is Nicole Kidman. She wouldn't have it any other

way. One thing we knew we always wanted on THE HOURS was to have not only a

coherence and unity in the overall look and design of the film, but at the same

time to have a different and distinctive look from story to story. There is a

visual opposition at work between the lives of the three women – and a lot of

that is done with simple elements such as color. We used a different palette

for Meryl, Julianne and Nicole but simultaneously, the colors in each of their

stories refer back to one another, providing little echoes from scene to scene.

We did similar things with camera movements and film processing techniques –

giving each woman and era a unique look yet one that is always tied to the next

story and the next moment in time. In the end, I think the film calls for a

very complex emotional reaction, and a different reaction to each story. One

thing that really interested me is the exploration of the mother-son

relationship, which is very complex, and comes to the fore in the story of

Laura Brown. In this case, you have a child who is literally deserted by his mother

– "abandoned" is the word that the mother herself uses. And our

individual response to that sort of act comes from a political, moral and

emotional place, especially because in our society mothers who leave their

children are judged severely. I think the response of each audience member to

Laura’s story will be different depending on their own personal experience or

personal knowledge of that sort of situation. But no matter where you are

starting from, I think everyone can relate in some way to the mother-son

relationship and will feel how potent it is and will be engaged by it. Another

interesting role many people will be able to relate to is that of Clarissa Vaughan

as the woman who looks after others in the hopes that creating happiness for

someone else will in turn create more meaning in her own life. There are

millions and millions of "carers" in this world who go unsung and

unexplored for the most part. I think many people will have a strong reaction

to Clarissa and the consequences of her choices. And then of course there is

Virginia Woolf, who is willing to literally risk her own sanity, risk

descending into madness, as an essential element in the creative process –

another choice that is open to debate and different responses. In this sense,

the film really is an exploration of women in the 20th century and the difficult,

sometimes heartbreaking, choices that they have had to make. For Laura, Clarissa

and Virginia Woolf, the choices are literally a matter between death and celebrating

life.

FROM NOVEL TO FILM - Author Michael

Cunningham on THE HOURS

I may be the only living American novelist who is entirely happy with

what Hollywood has done to his novel. I naturally feel slightly embarrassed

about that. I worry that if I were a more substantial person, I’d be outraged. And

yet. They did a remarkable job. I felt good about the movie from the beginning,

when Scott Rudin told me that David Hare was interested in writing the

screenplay. I find that, unlike many novelists, I don’t feel much allegiance to

the “sacred text”. A novel, any novel, I write is neither more nor less than

the best I could do right then with those characters and situations. Five or

more years later, I’d surely write the book differently. If I’m fortunate

enough to find that someone gifted and intelligent, “someone I respect,“ wants

to turn my story into a movie or an opera or a situation comedy, the only

sensible response is to turn it over and see where he or she will take the

story, and to hope that I’ll be surprised. I wouldn’t want an entirely faithful

adaptation. What would be the fun of that? Before David started writing, I

spent a day with him and Stephen Daldry, the director, in London. We talked for

hours about the characters’ lives outside the scope of the book: How did

Clarissa and Sally meet? Had Richard been an AIDS activist? If Laura were to

truly consider taking her own life, what means would she use? Then, armed with

that information, David went to work, very much on his own. As it turns out,

the movie version of “The Hours” is pretty close to the book. David has told me

that he tried it all sorts of ways, and found that the book’s existing

structure seemed to work best. The brilliance of his screenplay resides, in

large part, in the transitions “we move effortlessly among the three different

stories “ and in the translation into scenes of that which was interior in the

book. Without in any way simplifying the characters or their situations, he

found things for them to do and say, ways for them to interact that telegraph

the states of their souls. It’s revelatory, too, to see the actors at work. On one

hand, in translating a book into film, you lose the capacity to go inside the

character’s minds, and that of course is a serious handicap. But on the other

hand you get Meryl Streep cracking an egg with barely suppressed violence,

Nicole Kidman looking at a child as if from the depths of hell itself, Julianne

Moore weeping in a bathroom while speaking cheerfully to her husband in the

next room. These wonders are available only from actors, and they make up for many

pages worth of interiority. As I try to write concisely about the experience of

seeing THE HOURS, the novel, turned into “The Hours”, the movie, I better

understand those flustered Oscar winners who have to acknowledge more people,

all of them essential, than they can possibly get to before the band starts

playing them offstage. Any movie is hard to make; a good movie is almost

impossible, and when a good movie gets made, almost everyone involved has

brought some necessary spark of brilliance. Philip Glass’s music functions in

the movie very much the way language does in a novel, as a rhythmic and lyrical

accompaniment, and occasionally a counterpoint, to the raw business of the

story. The music in THE HOURS is a stronger presence than music ordinarily is

in movies it’s meant as more than background. It’s as integral to the action as

sentences are in a novel. Some people are put off by the prominence of the

music. I think it’s revolutionary, and exactly right. The set designs and

cinematography are breathtaking. Look for the close-up of the bird in the

garden. And, finally, Stephen Daldry is some kind of genius. He pulled if off.

It wasn’t easy. When you see the movie, look for little unifying gestures that

are common to all three stories, not just flowers and cooking but more subtle

bits of business. Everyone cracks an egg. Everyone loses a shoe. It is just

this sort of invisible stitching on which narrative stands. In short, they did

the nearly impossible. They produced a work of art. I can still hardly believe

my luck.