| Orwell: is the socialism possible? | ||||

|

|

||||

*June

25, 1903 Motihari - India *June

25, 1903 Motihari - India

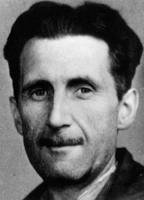

+ January 21, 1950 London - GB Eric Arthur Blair (later George Orwell) was born in 1903 in the Indian village of Motihari, which lies near the border of Nepal. At that time India was a part of the British Empire, and Blair's father, Richard, held a post as an agent in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service. The Blairs led a relatively privileged and fairly pleasant life, helping to administer the Empire. The Blair family was not very wealthy - Orwell later described them ironically as "lower-upper-middle class". In 1907, when Eric was about eight years old, the family returned to England and lived at Henley, though the father continued to work in India until he retired in 1912. With some difficulty, Blair's parents sent their son to a private preparatory school in Sussex at the age of eight. At the age of thirteen he won a scholarship to Wellington, and soon after, another to Eton, the famous public school. He had finished the final examinations at Eton as number 138 of 167. He neglected to win a university scholarship, and in 1922 Eric Blair joined the Indian Imperial Police. In doing so he was already breaking away from the path most of his school-fellows would take, for Eton often led to either Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, he was drawn to a life of travel and action. He trained in Burma, and served there in the police force for five years. In 1927, while home on leave, he resigned. Back in London he settled down in a grotty bedroom in Portobello Road. There, at the age of twenty-four, he started to teach himself how to write. His neighbours were impressed by his determination . Week after week he remained in his unheated bedroom, thawing his hands over a candle when they became too numb to write. In spring of 1928, he turned his back on his own inherited values by taking a drastic step. For more than one year he lived among the poor, first in London, then in Paris. In Paris he lived and worked in a working-class quarter. At that time, Paris was full of artists and would-be artists. There Orwell led a life that was far from bohemian; when he eventually got a job, he worked as a dishwasher. When he returned to London, he lived for a couple of months among

the tramps and poor people there. Orwell's reasons for taking the name Orwell are much more complicated than those that writers usually have when adopting a pen-name. In effect, it meant that Eric Blair would somehow have to shed his old identity and take on a new. This is exactly what he tried to do: he tried to change himself from Eric Blair, old Etonian and English colonial policemen, into George Orwell, classless anti-authoritarian. He went to Spain at the end of 1936, with the idea of writing newspaper articles on the Civil War, which had broken out there. The conflict in Spain was between the communist, socialist Republic, and General Franco's Fascist military rebellion. When Orwell arrived in Barcelona he was astonished by the atmosphere he found there: what had seemed impossible in England seemed a fact of daily life in Spain. Class distinctions seemed to have vanished. There was a shortage of everything, but there was equality. Orwell joined in the struggle by enlisting in the militia of the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación de Marxista), which was associated with the British Labour Party For the first time in his life socialism seemed a reality, something for which it was worth fighting for. Orwell received a basic military training and was sent to the front in Aragon, near Zaragoza. He spent a couple of dull months there, and he was wounded in the throat. Three and a half months later, when he returned to Barcelona, he found it a changed city. No longer a place where the socialist word "comrade" was really felt to mean something, it was a city returning to "normal". Even worse, he was to find that the group he was with, the POUM, was now accused of being a Fascist militia, secretly helping Franco. Orwell had to sleep in the open to avoid showing his papers, and eventually managed to escape into France with his wife. His account of his time in Spain was published in Homage to Catalonia (1938). His experiences in Spain left two impressions on Orwell's mind: firstly, they showed him that socialism in action was a human possibility, if only a temporary one. He never forgot the exhilaration of those first days in Barcelona, when a new society seemed possible, where "comradeship", instead of being just a socialist abuse of language, was reality. But secondly he saw the experience of the city returning to normal as a gloomy confirmation of the fact that there will always be different classes, that there is something in the human nature that seeks violence, conflict, power over others. It is clear that these two impressions, of hope on the one hand, and despair on the other are entirely contradictory. Nevertheless, despite the despair and confusion of his return to Barcelona (there were street fights between different groups of socialists), Orwell left Spain with a hopeful impression.

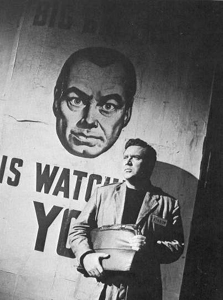

1984 Big Brother Big Brother is not a real person. All-present as he is, all-powerful and forever watching, he is only seen on TV. Although his picture glares out from huge posters that shout, BIG BROTHER IS WATCHING YOU, nobody sees Big Brother in person. Orwell had several things in mind when he created Big Brother. He was certainly thinking of Russian leader Joseph Stalin; the pictures of Big Brother even look like him. He was also thinking of Nazi leader Adolph Hitler and Spanish dictator Francisco Franco. Big Brother stands for dictators everywhere. Orwell may have been thinking about figures in certain religious faiths when he drew Big Brother. The mysterious, powerful, God-like figure who sees and knows everything - but never appears in person. To Inner Party members, Big Brother is a leader, a bogeyman they can use to scare the people, and their authorisation for doing whatever they want. If anybody asks, they can say they are under orders from Big Brother. For the unthinking proles, Big Brother is a distant authority figure. For Winston, Big Brother is an inspiration. Big Brother excites and energises Winston, who hates him. He is also fascinated by Big Brother and drawn to him in some of the same ways that he is drawn to O'Brien, developing a love-hate response to both of them that leads to his downfall. The Party The Party of Oceania is made up of about 19% of the whole population of Oceania's mainland. Generally, one could divide the Party into the Inner Party, which is comparable to the communist nomenclature, and the Outer Party. Winston Smith himself is a member of the Outer Party. The members of the Inner Party hold high posts in the administration of the country. They earn comparably much money, and there isn't a lack of anything in their homes, which look like palaces. The people of the Outer Party live in dull grey and old flats. Because of the war there is often a lack of the most essential things. The life of the Outer Party is dictated by the Party, even their spare time is used by the Party. There are so-called community hikes, community games and all sorts of other activities. And refusing participation in this activities is even dangerous. The life of a Party member is dictated from his birth to his death. The Party even takes children away from their parents to educate them in the ideology of Ingsoc. (One can find this also in the communist future plans.) The children are taught in school to report it to the Thought Police when their parents have unorthodox thoughts, so-called "thoughtcrimes". After their education, Party members start to work mainly for one of the four Ministries (Minipax, Minitrue, Miniluv, Miniplenty). The further life of a "comrade" continues under the watchful eyes of the Party. Everything people do is recorded by the telescreens. Even in their homes people have telescreens. Each unorthodox action is then punished by "joycamps" (Newspeak word for "forced labour camps"). Proles The proles make up about 81% of the population of Oceania. The Party itself is only interested in their labour, because the proles are mainly employed in industry and on farms. Without their labour, Oceania would break down. Despite this fact, the Party completely ignores this social caste. The curious thing about this behaviour is that the Party calls itself socialist, and generally socialism (at least in the beginning and middle of this century) is a movement of the proletariat. So one could say that the Party abuses the word "Ingsoc". Orwell again had pointed at another regime, the Nazis, who had put "socialism" into their name. One of the main phrases of the Party is "Proles and animals are free". In Oceania, the proles live in very desolate and poor quarters. Compared with the districts where the members of the Party live, there are far fewer telescreens, and policemen. And as long as the proles don't commit crimes (crimes in our sense, not in the sense of the party - Thoughtcrime) they don't have any contact with the state. Therefore in the districts of the proletarians one can find things that are abolished and forbidden to Party members. For example, old books, old furniture, prostitution and alcohol (mainly beer) Except "Victory Gin" all of these things are not available to Party members. The proletarians don't participate in the technological development. They live like they used to do many years ago. To my mind, the Party ignores the Proles because they pose no danger to their rule. The working class is too uneducated and too unorganised to pose any real threat. So there is not really a need to change the political attitudes of this class. Newspeak Newspeak is the official language of Oceania and has been devised to meet ideological needs of Ingsoc, or English Socialism. In the year 1984, nobody really uses Newspeak in speech nor in writing. Only the leading articles are written in this "language". But it is generally assumed that in the year 2050 Newspeak will replace Oldspeak, or common English. The purpose of Newspeak is not only to provide a medium of expression for the world-view and mental habits proper to devotees of Ingsoc, but to make all other methods of thought impossible. Another reason for developing Newspeak is to make old books, or books which were written before the era of the Party, unreadable. With Newspeak, Doublethink will be even easier. Its vocabulary is constructed so as to give exact and often very subtle expression to every meaning that a Party member could properly wish to express, while excluding all other meanings and also the possibility of arriving at them by indirect methods. This is done partly by the invention of new words, but chiefly by eliminating undesirable words by stripping such words as remained of unorthodox meanings whatever. Generally Newspeak words are divided into three groups: the A, B(also called compound words) and the C Vocabulary. Doublethink

Symbolism In "Nineteen Eighty-Four" Orwell draws a picture of a totalitarian future. Although the action takes place in the future, there are a couple of elements and symbols taken from the present and past. So, for example, Emmanuel Goldstein, the main enemy of Oceania, is, as one can see from the name, a Jew. Orwell draws a link to other totalitarian systems of our century, like the Nazis and the Communists, who had anti-Semitic ideas, and who used Jews as so-called scapegoats, who were responsible for all bad and evil things in the country. This fact also shows that totalitarian systems want to arbitrate their perfection. Emmanuel Goldstein somehow also stands for Trotsky, a leader of the Revolution, who was later declared an enemy. Another symbol that can be found in Nineteen Eighty-Four is the fact that Orwell divides the fictional superstates in the book according to the division that can be found during the Cold War. So Oceania stands for the United States of America , Eurasia for Russia and Eastasia for China. The fact that the two socialist countries Eastasia and Eurasia (in our case Russia and China) are at war with each other, corresponds to our history (Usuri river). Other, non-historical symbols can be found. One of these symbols is the paperweight that Winston buys in the old junk-shop. It stands for the fragile little world that Winston and Julia have made for each other. They are the coral inside of it. As Orwell wrote: "It is a little chunk of history, that they have forgotten to alter". The "Golden Country" is another symbol. It stands for the old European pastoral landscape. The place where Winston and Julia meet for the first time to make love to each other, is exactly like the "Golden Country" of Winston's dreams.

The novel Animal Farm is a satire of the Russian revolution, and therefore full of symbolism. Generally, Orwell associates certain real characters with the characters of the book. Here is a list of the characters and things and their meaning: Mr Jones: Mr Jones is one of Orwell's major (or at least most obvious) villain in Animal Farm. Orwell says that at one time Jones was actually a decent master to his animals. At this time the farm was thriving. But in recent years the farm had fallen on harder times and the opportunity was seen to revolt. The world-wide depression began in the United States when the stock market crashed in October of 1929. The depression spread throughout the world because American exports were so dependent on Europe. The U.S. was also a major contributor to the world market economy. Germany along with the rest of Europe was especially hard hit. The parallels between crop failure of the farm and the depression in the 1930s are clear. Only the leaders and the die-hard followers ate their fill during this time period. Mr Jones symbolises (in addition to the evils of capitalism) Czar Nicholas II, the leader before Stalin (Napoleon). Jones represents the old government, the last of the Czars. Orwell suggests that Jones was losing his "edge". In fact, he and his men had taken up the habit of drinking. Old Major reveals his feelings about Jones and his administration when he says, "Man is the only creature that consumes without producing. He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals. He sets them to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving and the rest he keeps for himself." So Jones and the old government are successfully uprooted by the animals. Little do they know history will repeat itself with Napoleon and the pigs. Old Major: Old Major is the first major character described by Orwell in Animal Farm. This "pure-bred" of pigs is the kind, grandfatherly philosopher of change - an obvious metaphor for Karl Marx. Old Major proposes a solution to the animals' desperate plight under the Jones "administration" when he inspires a rebellion of sorts among the animals. Of course the actual time of the revolt is untold. It could be the next day or several generations down the road. But Old Major's philosophy is only an ideal. After his death, three days after the barn-yard speech, the socialism he professes is drastically altered when Napoleon and the other pigs begin to dominate. It's interesting that Orwell does not mention Napoleon or Snowball at any time during the great speech of old Major. This shows how distant and out-of-touch they really were; the ideals Old Major proclaimed seemed to not even have been considered when they were establishing their new government after the successful revolt. It almost seems as though the pigs fed off old Major's inspiration and then used it to benefit themselves (an interesting twist of capitalism) instead of following through on the old Major's honest proposal. This could be Orwell's attempt to dig Stalin, whom many consider to be someone who totally ignored Marx's political and social theory. Using Old Major's apparent naivety, Orwell concludes that no society is perfect, no pure socialist civilisation can exist, and there is no way to escaping the evil grasp of capitalism. (More on this in the Napoleon section.) Unfortunately, when Napoleon and Squealer take over, old Major becomes more and more a distant fragment of the past in the minds of the farm animals. Napoleon: Napoleon is Orwell's chief villain in Animal Farm. The name Napoleon is very appropriate since Napoleon, the dictator of France, was thought by many to be the Anti-Christ. Napoleon, the pig, is really the central character on the farm. Obviously a metaphor for Stalin, Comrade Napoleon represents the human frailties of any revolution. Orwell believed that although socialism is good as an ideal, it can never be successfully adopted due the to uncontrollable sins of human nature. For example, although Napoleon seems at first to be a good leader, he is eventually overcome by greed and soon becomes power-hungry. Of course, Stalin did, too, in Russia, leaving the original equality of socialism behind, giving himself all the power and living in luxury while the common peasant suffered. Thus, while his national and international status blossomed, the welfare of Russia remained unchanged. Orwell explains, "Somehow it seemed as though the farm had grown richer without making the animals themselves any richer--except, of course for the pigs and the dogs." The true side of Napoleon becomes evident after he slaughters so many animals for plotting against him. He even hires a pig to sample his food for him to make certain that no one is trying to poison him. Stalin, too, was a cruel dictator in Russia. After suspecting many people in his empire to be supporters of Trotsky (Orwell's Snowball), Stalin systematically murdered many. At the end of the book, Napoleon doesn't even pretend to lead a socialist state. After renaming it a Republic and instituting his own version of the commandments and the Beasts of England, Comrade Napoleon quickly becomes more or less a dictator who of course has never even been elected by the animals. Squealer: Squealer is an intriguing character in Orwell's Animal Farm. He's first described as a manipulator and persuader. Orwell narrates, "He could turn black into white." Many critics correlate Squealer with the Pravda, the Russian newspaper of the 1930s. Propaganda was a key to many publications, and since there was no television or radio, the newspaper was the primary source of media information. So the monopoly of the Pravda was seized by Stalin and his new Bolshevik regime. In Animal Farm, Squealer, like the newspaper, is the link between Napoleon and other animals. When Squealer masks the evil intentions of the pigs, the intentions can be carried out with little resistance and without political disarray. Squealer is also thought by some to represent Goebbels, who was the minister of propaganda for Germany. This would seem inconsistent with Orwell's satire, however, which was supposed to metaphor characters in Russia. Snowball: Orwell describes Snowball as a pig very similar to Napoleon at least in the early stages. Both pigs wanted a leadership position in the "new" economic and political system (which is actually contradictory to the whole supposed system of equality). But as time passes, both eventually realise that one of them will have to step down. Orwell says that the two were always arguing. "Snowball and Napoleon were by far the most active in the debates. But it was noticed that these two were never in agreement: whatever suggestion either of them made, the other could be counted to oppose it." Later, Orwell makes the case stronger. "These two disagreed at every point disagreement was possible." Soon the differences, like whether or not to build a windmill, become too great to deal with, so Napoleon decides that Snowball must be eliminated. It might seem that this was a spontaneous reaction, but a careful look tells otherwise. Napoleon was setting the stage for his own domination long before he really began "dishing it out" to Snowball. For example, he took the puppies away from their mothers in an effort to establish a private police force. These dogs would later be used to eliminate Snowball, his arch-rival. Snowball represents Leo Trotsky, the arch-rival of Stalin in Russia. The parallels between Trotsky and Snowball are uncanny. Trotsky too, was exiled, not from the farm, but to Mexico, where he spoke out against Stalin. Stalin was very weary of Trotsky and feared that Trotsky supporters might try to assassinate him. The dictator of Russia tried hard to kill Trotsky, for the fear of losing leadership was very great in the crazy man's mind. Trotsky also believed in communism, but he thought he could run Russia better than Stalin. Trotsky was murdered in Mexico by the Russian internal police, the NKVD - the precursor of the KGB. Trotsky was found with a pick axe in his head at his villa in Mexico. Boxer: The name Boxer is cleverly used by Orwell as a metaphor for the Boxer Rebellion in China in the early twentieth century. It was this rebellion which signalled the beginning of communism in red China. This form of communism, much like the distorted Stalin view of socialism, is still present today in the oppressive socialist government in China. Boxer and Clover are used by Orwell to represent the proletariat, or unskilled labour class in Russian society. This lower class is naturally drawn to Stalin (Napoleon) because it seems as though they will benefit most from his new system. Since Boxer and the other low animals are not accustomed to the "good life," they can't really compare Napoleon's government with the life they had before under the czars (Jones). Also, since usually the lowest class has the lowest intelligence, it is not difficult to persuade them into thinking they are getting a good deal. The proletariat is also quite good at convincing themselves that communism is a good idea. Orwell supports this contention when he narrates, "Their most faithful disciples were the two carthorses, Boxer and Clover. Those two had great difficulty in thinking anything out for themselves, but having once accepted the pigs as their teachers, they absorbed everything that they were told, and passed it on to the other animals by simple arguments." Later, the importance of the proletariat is shown when Boxer suddenly falls and there is suddenly a drastic decrease in work productivity. But still he is taken for granted by the pigs, who send him away in a glue truck. Truly Boxer is the biggest poster-child for gullibility. Pigs: Orwell uses the pigs to surround and support Napoleon. They symbolise the communist party loyalists and the friends of Stalin, as well as perhaps the Duma, or Russian parliament. The pigs, unlike other animals, live in luxury and enjoy the benefits of the society they help to control. The inequality and true hypocrisy of communism is expressed here by Orwell, who criticised Marx's oversimplified view of a socialist, "utopian" society. Obviously, George Orwell doesn't believe such a society can exist. Toward the end of the book, Orwell emphasises, "Somehow it seemed as though the farm had grown richer without making the animals themselves any richer except, of course, the pigs and the dogs." Dogs: Orwell uses the dogs in his book, Animal Farm, to represent the KGB or perhaps more accurately, the bodyguards of Stalin. The dogs are the arch-defenders of Napoleon and the pigs, and although they don't speak, they are definitely a force the other animals have to reckon with. Orwell almost speaks of the dogs as mindless robots, so dedicated to Napoleon that they can't really speak for themselves. This contention is supported as Orwell describes Napoleon's early and suspicious removal of six puppies from their mother. The reader is left in the dark for a while, but is later enlightened when Orwell describes the chase of Snowball. Napoleon uses his "secret dogs" for the first time here; before Snowball has a chance to stand up and give a counter-argument to Napoleon's disapproval of the windmill, the dogs viciously attack the pig, forcing him to flee, never to return again. Orwell narrates, "Silent and terrified, the animals crept back into the barn. In a moment the dogs came bounding back. At first no one had been able to imagine where these creatures came from, but the problem was soon solved: they were the puppies whom Napoleon had taken away from their mothers and reared privately. Though not yet full-grown, they were huge dogs, and as fierce-looking as wolves. They kept close to Napoleon. It was noticed that they wagged their tails to him in the same way as the other dogs had been used to do to Mr Jones." The use of the dogs begins the evil use of force which helps Napoleon maintain power. Later, the dogs do even more dastardly things when they are instructed to kill the animals labelled "disloyal." Stalin, too, had his own special force of "helpers". Really there are followers loyal to any politician or government leader, but Stalin in particular needed a special police force to eliminate his opponents. This is how Trotsky was killed. Mollie: Mollie is one of Orwell's minor characters, but she represents something very important. Mollie is one of the animals who is most opposed to the new government under Napoleon. She doesn't care much about the politics of the whole situation; she just wants to tie her hair with ribbons and eat sugar, things her social status won't allow. Many animals consider her a traitor when she is seen being petted by a human from a neighbouring farm. Soon Mollie is confronted by the "dedicated" animals, and she quietly leaves the farm. Mollie characterises the typical middle-class skilled worker who suffers from this new communism concept. No longer will she get her sugar (nice salary) because she is now just as low as the other animals, like Boxer and Clover. Orwell uses Mollie to characterise the people after any rebellion who aren't too receptive to new leaders and new economics. There are always those resistant to change. This continues to dispel the belief Orwell hated and according to which basically all animals act the same. The naivety of Marxism is criticised, socialism is not perfect, and it doesn't work for everyone. Moses: Moses is perhaps Orwell's most intriguing character in Animal Farm. This raven, first described as the "especial pet" of Mr Jones, is the only animal who doesn't work. He's also the only character who doesn't listen to Old Major's speech of rebellion. Orwell narrates, "The pigs had an even harder struggle to counteract the lies put about by Moses, the tame raven. Moses, who was Mr Jones's especial pet, was a spy and a tale-bearer, but he was also a clever talker. He claimed to know of the existence of a mysterious country called Sugarcandy Mountain, to which all animals went when they died. It was situated somewhere up in the sky, a little distance beyond the clouds, Moses said. In Sugarcandy Mountain it was Sunday seven days a week, clover was in season all the year round, and lump sugar and linseed cake grew on the hedges. The animals hated Moses because he told tales and did no work but some of them believed in Sugarcandy Mountain, and the pigs had to argue very hard to persuade them that there was no such place." Moses represents Orwell's view of the Church. To Orwell, the Church is just used as a tool by dictatorships to keep the working class of people hopeful and productive. Orwell uses Moses to criticize Marx's belief that the Church will just go away after the rebellion. Jones first used Moses to keep the animals working, and he was successful in many ways before the rebellion. The pigs had a real hard time getting rid of Moses, since the lies about Heaven they thought would only lead the animals away from the equality of socialism. But as the pigs led by Napoleon become more and more like Mr Jones, Moses finds his place again. After being away for several years, he suddenly returns and picks up right where he left off. The pigs don't mind this time because the animals have already realised that the "equality" of the revolt is a farce. So Napoleon feeds Moses with beer, and the full circle is complete. Orwell seems to offer a very cynical and harsh view of the Church. This proves that Animal Farm is not simply an anti-communist work meant to lead people into capitalism and Christianity. Really Orwell found loop-holes and much hypocrisy in both systems. It's interesting that recently in Russia the government has begun to allow and support religion again. It almost seems that like the pigs, the Kremlin officials of today are trying to keep their people motivated, not in the ideology of communism, but in the "old-fashioned" hope of an after-life. Muriel: Muriel is a knowledgeable goat who reads the commandments for Clover. Muriel represents the minority of working class people who are educated enough to decide things for themselves and find critical and hypocritical problems with their leaders. Unfortunately for the other animals, Muriel is not charismatic or inspired enough to take action and oppose Napoleon and his pigs. Old Benjamin: Old Benjamin, an elderly donkey, is one of Orwell's most elusive and intriguing characters on Animal Farm. He is described as rather unchanged since the rebellion. He still does his work the same way, never becoming too excited or too disappointed about anything that has passed. Benjamin explains, "Donkeys live a long time. None of you has ever seen a dead donkey." Although there is no clear metaphoric relationship between Benjamin and Orwell's critique of communism, it makes sense that during any rebellion there are those who never totally embrace the revolution, those so cynical they no longer look to their leaders for help. Benjamin symbolises the older generation, the critics of any new rebellion. Really this old donkey is the only animal who seems as though he couldn't care less about Napoleon and Animal Farm. It's almost as if he can see into the future, knowing that the revolt is only a temporary change, and will flop in the end. Benjamin is the only animal who doesn't seem to have expected anything positive from the revolution. He almost seems on a whole different maturity level compared with the other animals. He is not sucked in by Napoleon's propaganda like the others. The only time he seems to care about the others at all is when Boxer is carried off in the glue truck. It's almost as if the old donkey finally comes out of his shell, his perfectly fitted demeanour, when he tries to warn the others of Boxer's fate. And the animals do try to rescue Boxer, but it's too late. Benjamin seems to be finally confronting Napoleon and revealing his knowledge of the pigs' hypocrisy, although before he had been completely independent. After the animals have forgotten Jones and their past lives, Benjamin still remembers everything. Orwell states, "Only old Benjamin professed to remember every detail of his long life and to know that things never had been, nor ever could be much better or much worse; hunger, hardship, and disappointment being, so he said, the unalterable law of life." |

||||

![]() UK

UK

At his visit he announced that he was going to write a book about

his time in Paris. After two rejections from publishers Orwell wrote

Burmese Days (published in 1934), a book based on his experiences

in the colonial service.

At his visit he announced that he was going to write a book about

his time in Paris. After two rejections from publishers Orwell wrote

Burmese Days (published in 1934), a book based on his experiences

in the colonial service.  In

1939 the war between England and Germany broke out. Orwell wanted

to fight, as he has done in Spain, against the fascist enemy, but

he was declared physically unfit. In 1941 he joined the British

Broadcasting Corporation as talks producer in the Indian section

of the eastern service. He served in the Home Guard, a wartime civilian

body for local defence. In 1943 he left the BBC to become literary

editor of the Tribune and began writing Animal Farm. In 1944 the

Orwells adopted a son, but in 1945 his wife died during an operation.

Towards the end of the war, Orwell went to Europe as a reporter.

Late in 1945 he went to the island of Jura off the Scottish coast,

and settled there in 1946. He wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four there.

The island's climate was unsuitable for someone suffering from tuberculosis

and Nineteen Eighty-Four reflects the bleakness of human suffering,

the indignity of pain. Indeed, he said that the book wouldn't have

been so gloomy had he not been so ill. Later that year he married

Sonia Brownell. He died in January 1950.

In

1939 the war between England and Germany broke out. Orwell wanted

to fight, as he has done in Spain, against the fascist enemy, but

he was declared physically unfit. In 1941 he joined the British

Broadcasting Corporation as talks producer in the Indian section

of the eastern service. He served in the Home Guard, a wartime civilian

body for local defence. In 1943 he left the BBC to become literary

editor of the Tribune and began writing Animal Farm. In 1944 the

Orwells adopted a son, but in 1945 his wife died during an operation.

Towards the end of the war, Orwell went to Europe as a reporter.

Late in 1945 he went to the island of Jura off the Scottish coast,

and settled there in 1946. He wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four there.

The island's climate was unsuitable for someone suffering from tuberculosis

and Nineteen Eighty-Four reflects the bleakness of human suffering,

the indignity of pain. Indeed, he said that the book wouldn't have

been so gloomy had he not been so ill. Later that year he married

Sonia Brownell. He died in January 1950. Doublethink

is a kind of manipulation of the mind. Generally, one could say

that Doublethink makes people accept contradictions, and it makes

them also believe that the party is the only institution that distinguishes

between right and wrong. This manipulation is mainly done by the

Minitrue (Ministry of Truth), where Winston Smith works. When a

person that is well grounded in Doublethink recognizes a contradiction

or a lie by the Party, then the person thinks that he is remembering

a false fact. The use of the word Doublethink involves doublethink.

With the help of the Minitrue, it is not only possible to change

written facts, but also facts that are remembered by people. So

complete control of the country and its citizens is provided. The

fact of faking history had already been used by the Nazis, who told

the people that already German Knights believed in the principles

of National Socialism.

Doublethink

is a kind of manipulation of the mind. Generally, one could say

that Doublethink makes people accept contradictions, and it makes

them also believe that the party is the only institution that distinguishes

between right and wrong. This manipulation is mainly done by the

Minitrue (Ministry of Truth), where Winston Smith works. When a

person that is well grounded in Doublethink recognizes a contradiction

or a lie by the Party, then the person thinks that he is remembering

a false fact. The use of the word Doublethink involves doublethink.

With the help of the Minitrue, it is not only possible to change

written facts, but also facts that are remembered by people. So

complete control of the country and its citizens is provided. The

fact of faking history had already been used by the Nazis, who told

the people that already German Knights believed in the principles

of National Socialism. THE

ANIMAL FARM

THE

ANIMAL FARM